More Candombe

History of Uruguay’s Carnival, the Origins of Candombe

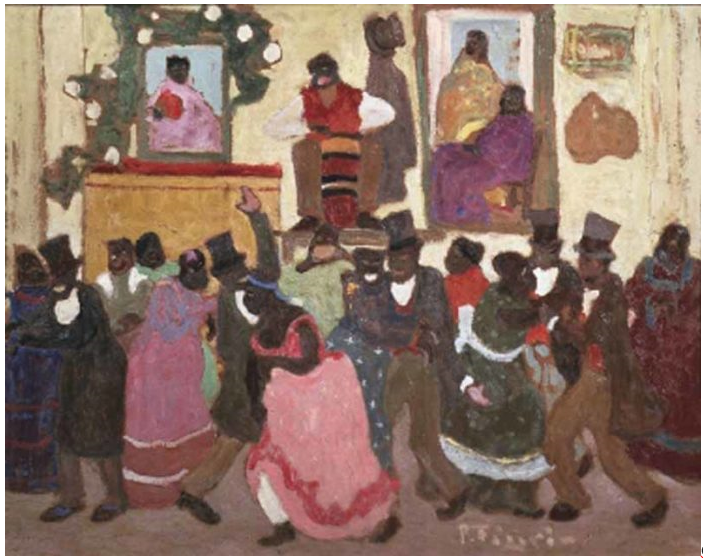

| The birth of candombe among the African slaves in the colonial era of nineteenth century Montevideo. Before President Joaquin Suarez abolished slavery on 1846 it was a common practice for Uruguayan households to employ African slaves for menial work. An estimate of ten million Africans reached the American continent’s harbours but it is believed that only one in six survived the trip. On 1750 the first African slaves arrived to Montevideo, eventually half the population of the country would be of African descent though they now number in the thousands. The African population was varied, 71% came from the Bantu area: Eastern and Equatorial Africa and the rest from Western Africa. Candombe is what little survives of the culture brought by the African slaves after the suppression of the Spanish. As an escape, the slaves would gather clandestinely and dance accompanied by drums made out of barrels called tangós. By extension the word tangó defined the dance and the place where they gathered as well. Candombe, by the brush of Pedro Figari, 1921 |

Meaning and Etymology of Candombe

The word candombe comes from the prefix Ka and the word Ndombe in Kimbundu language. This language belonged to the Bantu tongues that were spoken in Congo, Angola and other parts of southern Africa. The word was introduced by the population from Benguela in Angola, which were the principal Ndombe people among African ethnic groups in Montevideo.

Besides previous references by Montevideo’s Town Council to African’s dances, the first apparition of the word is in Montevideo’s El Universal newspaper on the 27 of November of 1834.

There are other sources attributed to candombe. For instance, the combination of the words Ka and Ndongue attributed to the Mandikan slaves from Sudan, who had a direct Egyptian influence. For Egyptians Ka was a manifestation of vital energies and an indissoluble part of the human being; probably akin to a soul.

The word Ndongue meant black but in a symbolic way: it represents the earth, resurrection, the fertility of the mud, the regeneration of the earth and therefore life. Egypt itself was called Black Earth.

Candombe in the 19th Century

Between the 25th of December and the 6th of January the local authorities allowed slaves to gather to sing and dance in the Market’s Square and the South’s Cube (Cubo del Sur); an emplacement for cannons at the south of Montevideo’s citadel wall. The slaves gathered in each neighbourhood for an indoors ceremony calling each other with drums, that being the origin of the Calls Parade.

Additionally, the assembled group in a procession, akin to nowadays comparsas, visited Montevideo’s authorities. The ceremonies and processions were the only way they had to keep their traditions and culture alive amidst the reigning European population.

By the end of the century candombe wasn’t a ceremony anymore. What remained was a dance were the dancers organized in a circle alternating men and women in no particular order; the dancers didn’t have partners. No rules were followed because the only requirement was the singing between the stick holder and the circle of dancers.

In the beginning, candombe wasn’t public, only relatives or close people were allowed. The dance would be interrupted in the presence of a stranger and substituted by meaningless dances and songs.

In the twentieth century candombe evolved to become as public and Uruguayan as drinking mate. What once was the repressed culture of the African slaves became a culture in itself that identifies the whole country and has spread beyond the humble borders of Uruguay. All along the carnival season, whether in the Carnival Competition or the parades, in theatres or in the street, candombe can be breathed in the Uruguayan air.